Taylor Swift does not exist

You might have recently heard that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—via SoftBank Kabushiki Gaisha, via its wholly-owned subsidiary Gannett, which owns USA Today alongside a sad little clutch of failing syndicated local newspapers—has hired the world’s first full-time Taylor Swift reporter. His name is Bryan, and I’m deeply upset. Not because I don’t think Taylor Swift is worth writing about. Taylor Swift is, by any sensible measure, the most famous person in the world. The actual leaders of actual countries beg her to visit their dying lands, put on a show, make their miserable people spend some of their miserable money, maybe nudge the whole economy just a few points out of recession. When a war breaks out in Asia, both sides immediately try to argue that they’re fighting on the side of Taylor Swift. She is bigger than Elvis, bigger than the Beatles, bigger than God. She has blasted herself on a jet of pure sugary Americana into every quiet crevice of global culture. She provides the texture of daily life for thirteen year old Indonesian girls with hijabs and hard scraping eyes. There are swathes of rebel bushland in central Africa where children tear the guts out the earth at gunpoint and the central government has no power at all—but Taylor Swift does. In my travels across China, the only Western music you’d ever hear playing anywhere belonged to Taylor Swift. She’s not a solitary human being; she’s Coca-Cola. She has fundamentally changed the inner workings of the record industry, show ticketing, intellectual property—why not? Let’s say music theory too. She invented tone. She invented pitch. Taylor Swift seems destined to be remembered by our drooling, mud-eating descendants as a kind of culture hero, the mythical source of everything left for them to inherit. First was she who plucked strings and made pleasant sounds. Who taught man to spin thread and mark the hours of the sun. She who scattered the stars in the sky. She’s kind of a big deal.

But I’m upset about Bryan for two reasons. The first reason, which I share with every other ageing media grouch, is that this Bryan is a proud and open fan of Taylor Swift. Which is dangerous! A question as self-evidently titanic as who Taylor Swift is and what she’s doing—this must absolutely not, in any circumstances, be left to a fan.

Look: consider this. There is a fairly large subculture out there of utterly miserable lonely young men who lack any kind of sex or companionship. Some of them have never held someone’s hand. Never hugged anyone. Never touched. So a few of them—not many, but it does happen—pick up guns and fire at random into crowds of people. They would like to feel the sense of dumb animal contentment you get when another warm and living human being touches your skin, but they can’t, and so they kill. This makes sense. What doesn’t make sense is the fact that overwhelmingly, these people make no effort whatsoever to meet other people. They say they want love and touch, badly enough to go on shooting sprees about it—but not badly enough to try. Much weirder territory here. Something’s gone wrong, but what? It makes sense to think of social problems in terms of people not getting what they want. This is the little engine that’s powered all of human history, from the dawn of agriculture until the day before yesterday: the uneven distribution of the surplus. But now, we’ve broken out of history and into something else, and the true nature of our problem is something much slipperier: not the repression of desire, but its disappearance. Hard to escape the conclusion that the incels don’t actually want sex at all; what they want is what they’re getting, which is the pleasure of being aggrieved. Not undesired, but undesiring: screenblasted, subsisting off Twitter and porn, like some deep sea sponge, feeding on the plankton of simulated sociality that snows down from above. Their murderous agony is that they are, secretly, perfectly content. And when they kill, it’s because it’s easier and more comfortable than peering into that vast calm absence of desire that swells where a living subject ought to be.

Anyway, it strikes me as very obvious that something similar is happening with the Taylor Swift fans: that they are, in a sense, female incels; that their manic love for and obsession with this woman is also screening an equally intense lack of desire. Taylor Swift is just the name that has been given to a certain blankness in the world. Consider: this is a woman whose most famous songs are all about breakups and ex-boyfriends. A significant portion of the news about Taylor Swift is the news about who she’s dating right now: the brain-damaged football player, the cackling edgelord, all those actors with their punchable faces… But you don’t believe—not to be too crude here, but you don’t believe she’s actually fucking these men, do you? Of course not. They have photoshoots together; that’s it. The life you see her lead is not her actual life. The feelings you hear her express are not her actual feelings. I’m not sure she actually has either. In the future, everyone will date Taylor Swift for fifteen minutes. When your number is called, you’ll go for a meal together, and she’ll be perfectly polite throughout, not icy, not even distant, but you will know, on an instinctive level you will know that this creature is utterly asexual, alibidinal, a synthetic product made in a sterile fac. And then you’ll go your separate ways, and she’ll write a song about you, and one billion psychotic teenagers will hate you for the rest of your life.

This is what distinguishes Taylor Swift from all the other white-girl pop stars of her cohort, the Katy Perrys and Miley Cyruses who used to be her equals a decade ago and who are, who knows, maybe even still alive somewhere: unlike them, she never sexualised herself. The others very obediently did everything to make themselves desirable, assuming that desire was a limitless resource: it’s not. You will have noticed that Taylor Swift’s fans are uniquely incapable of explaining what they actually like about her. Just that she writes her own lyrics, that it’s all so personal and relatable, that she is so much herself. But the rocks spinning silently in space are also themselves. This year, news outlets started reporting that people who had gone to see Taylor Swift’s Eras tour live were coming away with a strange, localised amnesia: after the concert, they’d suddenly realise that they couldn’t remember any specific thing that had happened. Very creepy! The BBC dragged out some psychologist to explain that this amnesia is caused by too much overwhelming stimulus, in too short a time for the brain to properly process it into memory, which is obvious pop-psych just-so-story drivel from a person who has no idea how a brain actually works. No: you don’t remember any specific events from the concert because there were no specific events. Just a vibrating slab of rich dark nothing.

I do not think the incels can ever adequately describe their own condition, because their condition is a screen that obscures what’s really at stake. Similarly, I don’t think any Swiftie can ever hope to adequately understand their idol. Taylor Swift is the formless crisis of the present and the void over which all things are spun. But all they can do is talk about her music, and her boyfriends, and her costumes, and her hair: things that simply do not, in any meaningful sense, exist.

The second reason I’m very upset about this Bryan character is that despite what everyone keeps saying, he is not, in fact, the world’s first full-time Taylor Swift reporter. The world’s first full-time Taylor Swift reporter was, as it happens, me.

I had the gig for just under four months, from October 2014 to late January 2015. Which is, I’ll admit, not a very long time, but it’s still longer than Bryan’s been on the job. This was for a print magazine, Kerfuffle, which some of you might remember, if only for its very high-profile closure. For those that don’t, Kerfuffle was the last real Gen-X hipster rag in London, printed every two weeks from a damp studio under a railway arch, on paper with the general tactile quality of cellophane. A typical issue of Kerfuffle would have basically disintegrated in your hands by the time it was finished, which was especially annoying for me because the editors had decided to stick my column on the last page. By the editors, I mostly mean John McCaran, who you’re probably aware of for other reasons, but who I mostly remember as a huge man with a prodigious coke habit, whose massive globed shoulders barely fit into the railway arch sideways. His main job, when it came to my writing, was to take whatever material I’d filed about supermarkets or reality TV or whatever, and go through it line by line, systematically deleting every reference to Theodor Adorno. Stop being so fucking clever, he told me. But I am clever, I said, I can’t help it. John liked my writing, once it had all its cleverness rinsed off, but he seemed to absolutely despise me. Maybe that was why he offered me the gig. Kerfuffle was, notionally, a music publication, but one of its gimmicks was that John would never assign a review to anyone who actually liked the particular kind of music in question. Paunchy old rockists got the A$AP Rocky album. Humanities graduates with green hair and a strong sense of justice were sent to interview neo-Nazi black metal bands. At the time, I was listening to a lot of early Swans and Einstürzende Neubauten and similar music for unhappy people. (I remember reading a YouTube comment under Raping a Slave, in which the commenter said that he’d recently found the help he needed and turned his life around, and he now found the music basically unlistenable. If anyone actually enjoyed this soul-crushing stuff, he said, it should be a wake-up call: something had gone badly wrong with our lives.) I got Taylor Swift.

Look: I was twenty-four years old, and John had offered me a monthly rate that was middling in retrospect but also represented more than I’d ever made from all the rest of my writing up to that point. And all I had to do was go to a bunch of Taylor Swift concerts, and maybe follow her around with the paps, and talk to some of her fans, and write about it all. She’d just released her career-defining album 1989; there was a lot of Taylor Swift to report on. (1989 is the year she was born; Taylor Swift and I are roughly the same age. I guess there are different ways of being twenty-four.) So for four months I did exactly that. And then in January I came back to London to spend another four months shivering in my bed and drinking cheap whiskey out the bottle and not replying to any of the concerned texts I kept getting from my friends. By the summer of 2015 I was well enough to rejoin the world. I stopped writing for Kerfuffle, which was just as well really. And I never really thought about my experience again, until Saudi Arabia appointed its Taylor Swift reporter this month, and I suddenly realised that I can remember taking the gig, and I can remember flying home in a state of psychotic frenzy, but I can remember absolutely nothing of the four months in between.

I did, of course, write about it all. But back issues of Kerfuffle are difficult to come by; a few editions have survived, even with their utterly lousy paper, but ever since John’s arrest, trial, and subsequent suicide while awaiting sentencing, there are very few people willing to stock them. I’d permanently deleted our entire email correspondence around the same time, which was deeply stupid of me but hopefully understandable given the circumstances. I’ve tried contacting record shops, vintage magazine collectors, and anyone else who might conceivably have a few issues knocking around, but nothing from October 2014 to January 2015 seems to be in circulation. (If you happen to have one of those issues, please, please get in touch.) For a moment I started to consider that maybe my real crackup wasn’t in 2015, but was happening right now. Had I simply imagined those four months on her trail? Was it all a morbid fantasy? Am I as sucked up in whatever sickness calls itself Taylor Swift as all her teeming, screaming fans?

I didn’t imagine it. It’s not a fantasy. My finished pieces might be gone forever, but I do still have my notes.

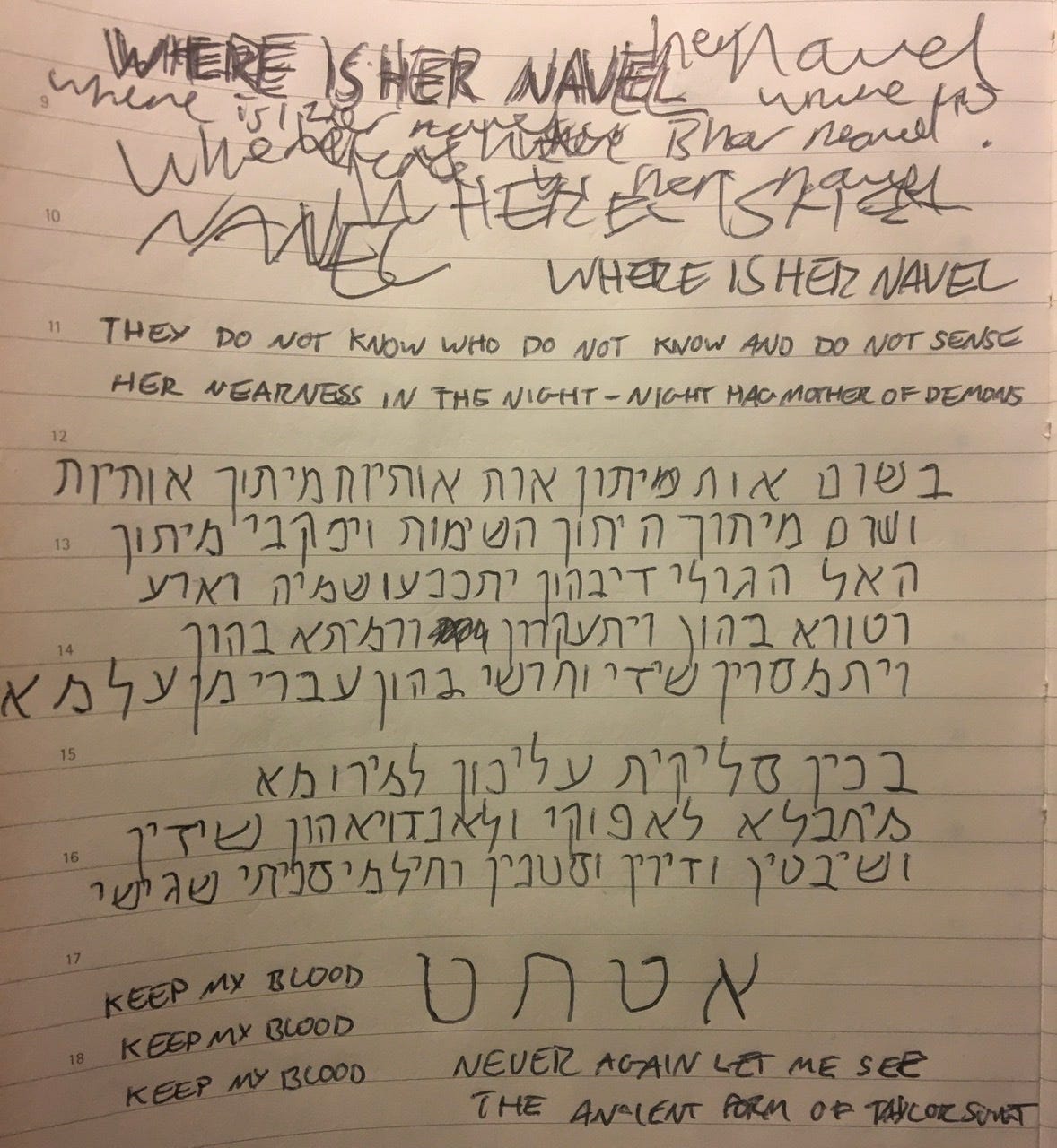

Annoyingly, there’s not a lot in there to suggest where I went or what I did during those four missing months of my life. (From my bank records, I’ve learned that I was withdrawing money from ATMs in New York City, Nashville, and—although I’m not sure why—Daviess County, Missouri.) Just a series of increasingly feverish scrawlings on the subject of Taylor Swift, like this one on her navel. It’s true: until early 2015, Taylor Swift made a point of never being photographed wearing anything that exposed her navel. The quote here is genuine, and the analysis I provide is, I think, some of the saner material in this particular notebook. The speculations that follow are significantly more deranged:

Again, Taylor Swift did indeed copyright many of the lyrics from 1989, including phrases like this sick beat and nice to meet you. It’s also true that human language in general has, in the near-decade since I scribbled these lines, increasingly become a medium for expressing statements about Taylor Swift. It was here that I started to get worried. I was clearly not well when I wrote this, but I was also right; in my madness I’d stumbled upon or prophesied something like the truth. Frustratingly, though, this is some of the last material that represents anything like a cogent thought or interpretation. What follows in my notebook are pages upon pages of annotated Taylor Swift lyrics, interspersed with quotations from other sources—the Bible, the Zohar, grimoires, goetic tracts—and, increasingly, mere paranoid gibberish:

The last entry was extremely disquieting to look at. It’s also only from mid-December, which means there’s another six weeks of my life that are entirely unaccounted for, in which I was wandering around with this stuff buzzing around in my head, or (given the general trend) something much worse. I dithered over whether or not I wanted to show this to you, but it’s significant. On the last page of my Taylor Swift journal, I returned to some of my earlier themes:

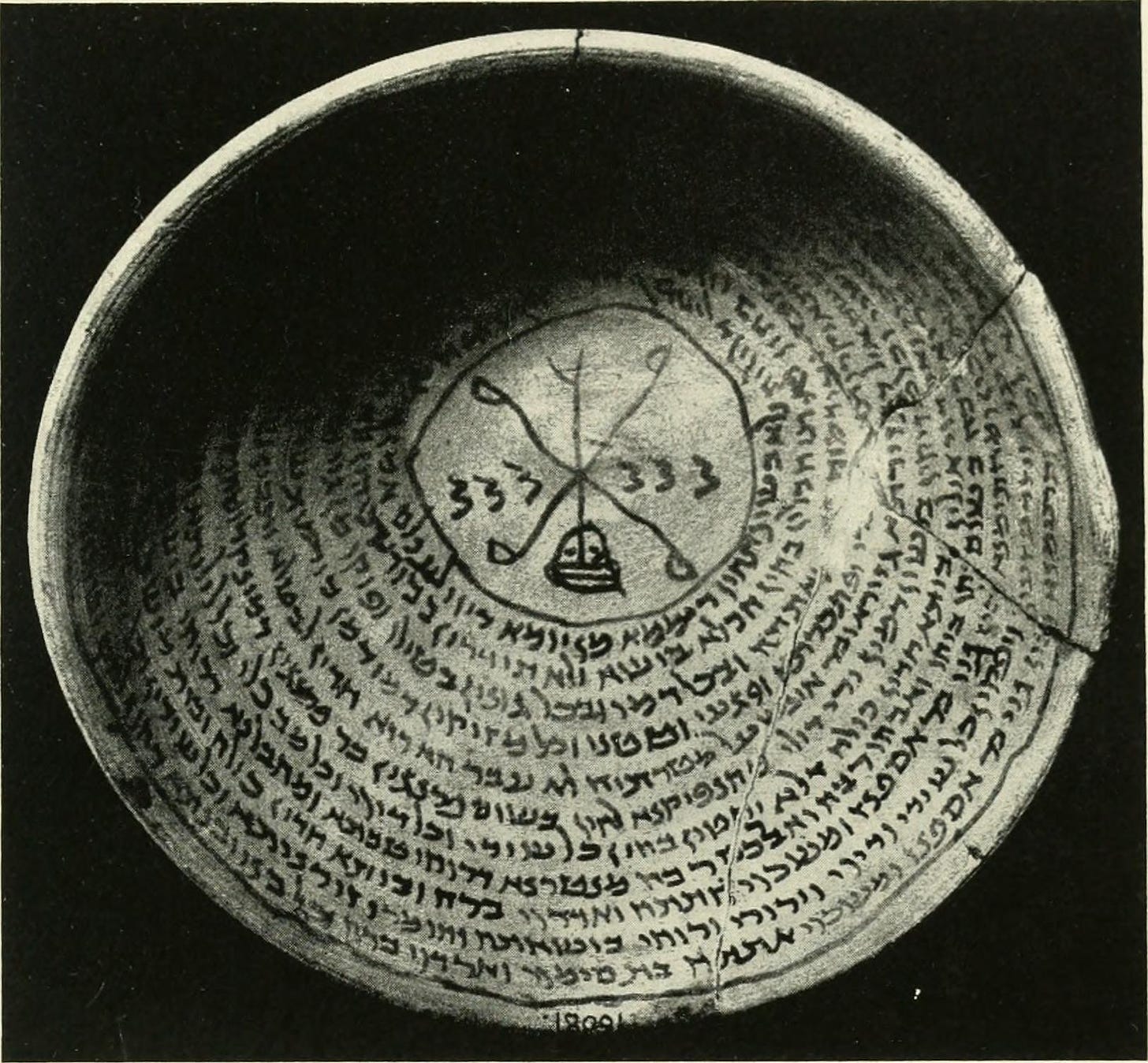

I showed the Hebrew text here to a few people who know the language better than I do, and they all told me it was a meaningless stew of letters. But it’s not, except for the final line—aleph, tet, chet, tet—which is the gematria for 1, 9, 8, and 9. The rest of the text above isn’t actually Hebrew at all: it’s Aramaic. And I managed to track down its origin. It’s from an incantation bowl, an apotropaic amulet popular among Babylonian Jews from the fourth to the sixth century. These bowls would be inscribed with spells against magical intruders, and usually buried in the foundations of a house. Here’s the bowl in question:

And the relevant English text:

In the name of a letter from within a letter and letters from within letters and a name from within the names and gaps from within the revealed, by which heaven and earth were subjugated, and by which mountains were uprooted, and by which heights were melted, and by which demons and sorceries pass from the world. Therefore, I ascended against you from on high to take out and banish all demons and plagues and dews and satans and all evil confused dreams.

What follows is entirely speculative. But I think—I think—I know what I was so afraid of here. Where is Taylor Swift’s navel? What does a navel mean? Well, as I suggested in my notes, a navel means separation from the amniotic unity of being; it marks the point where we have been torn away from the apeiron and into our limited, earthly selves. By not showing her navel, Taylor Swift was identifying herself with the infinite. But your navel also marks you out as a created being; it slots you into the grand chain of reproductive existence. And Taylor Swift was absconding from that too: she was positioning herself as something uncreated and eternal. Until, suddenly, she wasn’t.

On the 23rd of January, 2015, Taylor Swift posted a photo on Instagram of herself and the Haim sisters on the deck of a boat in Hawaii, all in bikinis. One of them was wearing a high-waisted bikini that covered her navel, but that person was not Taylor Swift. Her umbilicus was out. Two days later, I woke up as my plane landed at Heathrow, back in the same mnemic stream that I continue to inhabit today. Seeing her navel had snapped me out of whatever psychosis I was undergoing. Clearly, the deranged theory I’d nursed all those months was wrong.

Except—was it? According to the official story, the bikini pic came about because Taylor Swift and Haim had already been papped from another boat, and they decided to publish their own photo so the intruder wouldn’t get as much money for his. This is plausible. It’s also—given that we know how much of Taylor Swift’s apparent life is a total fabrication—very plausibly bullshit. Maybe Taylor Swift was deliberately debuting her navel. Maybe the reason she had not shown her navel until that day was because she didn’t have one.

There are two people who, by tradition, did not have navels. As Thomas Browne remarks in his Pseudodoxia Epidemica, ‘the Navel being a part, not precedent, but subsequent unto generation, nativity or parturition, it cannot be well imagined at the creation or extraordinary formation of Adam, who immediately issued from the Artifice of God; nor also that of Eve, who was not solemnly begotten, but suddenly framed, and anomalously proceeded from Adam.’ But in fact, there’s a weird discrepancy in the Biblical account of their creation. In Genesis 1, we read: ‘And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness, and they shall rule over the fish of the sea and over the fowl of the heaven and over the animals and over all the earth and over all the creeping things that creep upon the earth. And God created man in His image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.’ Very good. But then from Genesis 2:4, the creation happens again—except this time God creates man first, and then the plants, and then the animals, and only then does He finally create woman. ‘And the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon man, and he slept, and He took one of his sides, and He closed the flesh in its place. And the Lord God built the side that He had taken from man into a woman, and He brought her to man.’

So what gives? For some 250 years, the boring academic consensus has been that the Bible we have was cobbled together from various fragmentary sources that sometimes contradict each other, and you can tell that Genesis 1 and 2 had different authors because they give God different names. (Elohim or Yahweh, translated here as God or the Lord God.) But it’s much more interesting when people really try to make it make sense. There’s one interpretation, attributed in the Talmud to Rabbi Yirmeya ben Elazar, which I particularly like, which holds that the man of Genesis 1 was a kind of primordial hermaphrodite, a man and a woman joined together at the back. Then, as Genesis 2 relates, God sawed this creature in half, so its two faces could see each other. But Rabbi Yehuda bar Rabbi offers another account: God had actually made two separate women. When Adam sees Eve in Genesis 2:23, he says ‘This time, it is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh.’ Which does seem to imply that there was a previous time. The first time, Rabbi Yehuda says, Adam was not asleep while his companion was being created. He ‘saw her full of viscera and blood,’ and wanted nothing to do with her. That first companion, blood-filled, visceral, was called Lilith.

There are other versions of the story. In one, Adam doesn’t reject the first woman as soon as she’s created, but when he tries to fuck her she refuses to lie below him, since God had created them equal. They argue for a while, and then Lilith flees Paradise to give birth to demons. She and her brood still stalk the world, preying on men, stealing their seed in the night, putting curses on their children. The Aramaic incantation bowl above is a conjuration against Lilith. She turns up exactly once in the actual Bible, when Isaiah promises judgement on Edom. As the King James has it: ‘The cormorant and the bittern shall possess it; the owl also and the raven shall dwell in it: and he shall stretch out upon it the line of confusion, and the stones of emptiness… The satyr shall cry to his fellow; the screech owl also shall rest there.’ But the Hebrew text doesn’t say anything about any owls; the word it uses is lilith. Night-monster, night-hag, creature of blood and viscera who screeches when you should be asleep. She’s not always evil, exactly, but as a more recent interpreter points out, ‘Lilith and all beings similar to Lilith belong to a world from before the Fall, which means that human laws do not apply to them, that they’re not bound by human rules or human regulations, and that they don’t have human consciences or human hearts, and never shed human tears. For Lilith, there’s no such thing as sin. Their world is different. To human eyes, it might seem strange, as if drawn in a very fine line, since everything it contains is more luminous and lightweight.’ This is not to say she’s harmless. In medieval Christian depictions, the serpent that tempts Eve in the Garden is often portrayed as female, and sometimes with some very non-reptilian breasts. Lilith, the first devil, come to avenge herself on the one who replaced her.

Taylor Swift has, it’s worth mentioning, a longstanding association with snakes.

The primordial ex-girlfriend, the ex-girlfriend who hissed the magic of the earth at the very dawn of time. The spirit that refuses to simply lie underneath a man, that goes from house to house poisoning newborn infants, wiping out the fruits of desire. The great demon of indifference. The monster who—we can admit it—does sometimes seem to have right on her side. The one with no navel. She was not born; she did not Fall; she does not die. Pierced through the heart but never killed. Like every remnant of that other creation, she appears in ours in the form of a terrifying void. This is, I think, what I’d uncovered as the world’s first full-time Taylor Swift reporter.

I’m not saying any of this is true. I think that Taylor Swift is most likely an ordinary woman, thirty-three years old and not five thousand, seven hundred and eighty-four, who’s always had a belly button like everyone else, and whose private life is probably, like everyone else’s, just a little sad. But I believed it then. And it does make sense. It made enough sense to drive me mad.