An Opera About John Singer Sargent and a Male Model

Until the mid-nineteenth century, opera was wedded to rhythm and rhyme. Librettists supplied composers with heaps of verse for arias and other vocal numbers, alongside chunks of prose recitative that allowed for interstitial exposition. The convention began to break down with Wagner, who expanded recitative to epic proportions. In 1867, the Russian composer Alexander Dargomyzhsky took a further step, setting Pushkin’s blank-verse play “The Stone Guest” almost verbatim. Mussorgsky followed with “Boris Godunov,” a Pushkin adaptation on a monumental scale. Thus arose a genre that became known as Literaturoper, because nothing officially exists until it is named in German. Composers did not need librettists at all; they could make direct use of plays and other literary properties. Two formidable prose operas emerged just after 1900: Debussy’s “Pelléas et Mélisande,” a condensation of the play by Maurice Maeterlinck; and Strauss’s “Salome,” after the decadent drama by Oscar Wilde. This summer, Des Moines Metro Opera, one of America’s boldest smaller companies, staged those two works side by side, sending psychic shivers into the hot summer night.

Literaturoper rests on the assumption that opera suffers from excess artifice and that modern theatrical speech supplies a corrective. The justification was also musical: intensifying experiments in harmony and rhythm called for less form-bound texts. Debussy’s otherworldly sonorities, drifting away from the tonal system, uncannily matched Maeterlinck’s Symbolist prose. Mélisande’s entrance line—“Ne me touchez pas! Ne me touchez pas! ”—is a brittle recoil from an unwanted approach. Strauss, for his part, favored lunging melodic lines and stabbing dissonances. When the unhinged Herod enters mid-rant—“Where is Salome? Where is the Princess? Why did she not return to the banquet as I commanded her? Ah! There she is!”—notes splatter all around him, like wine spilling from his cup. In both cases, the composer releases the hidden music of the text.

Des Moines Metro Opera, which was founded in 1973, can’t rival Salzburg or Aix-en-Provence in scenic luxury. Yet musical values by no means suffer; casts are drawn from the upper ranks of younger American singers. And the company’s home venue—the Blank Performing Arts Center, on the campus of Simpson College, in Indianola—fosters unusual intimacy. The auditorium seats fewer than five hundred people, in an amphitheatre arrangement. The orchestra plays in a semi-enclosed pit, with the stage extending around it. The singers almost brush against those sitting in the front row. They can project without great effort and can be easily heard even when they have their backs turned. All of this enables conversational directness. Opera comes as close to straight theatre as I’ve seen it.

The snugness of the room worked especially well for “Pelléas,” a score that relies on suggestion, evasion, and ellipsis. The characters are at once archetypes and ciphers: the mysteriously meandering Mélisande; her grim groom, Golaud; and Golaud’s fatally solicitous half brother, Pelléas. The Des Moines production, directed by Chas Rader-Shieber, opted for a shadowy Victorian vibe, with surrealist touches. Wall panels and wardrobe doors opened to reveal, variously, a garden, a snowdrift, and a deer carcass hanging on a gambrel. The final tableau is bleakly potent: most everyone falls dead, and Golaud’s young son, Yniold, paces in circles, holding Mélisande’s newborn child.

What mattered most was the immediacy of the singing and the acting. The excellent young American bass-baritone Brandon Cedel, making his role début as Golaud, began tentatively, missing opportunities for nuance and color. A line like “I will never be able to find my way out of this forest” needs a twinge of fear. But as Golaud’s rage at Pelléas deepened Cedel applied vocal force by degrees, becoming uncomfortably menacing by the end. The agile baritone Edward Nelson, by contrast, was skittery, almost puckish, as Pelléas—he portrayed a charmer who has no awareness of the consequences of his charm. Sydney Mancasola, as Mélisande, brought to bear a luminous soprano and a grounded conception of the character; in place of a vacant damsel, she evoked a flesh-and-blood woman who has made a wrong turn into a damaged world. Matt Boehler was an imposing Arkel, Catherine Martin an affecting Geneviève. Derrick Inouye conducted with subtle authority. Emily Bieker’s flute solos beguiled the ears.

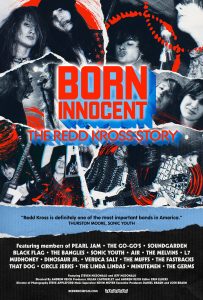

A nude study of Thomas Eugene McKeller, by John Singer Sargent (c. 1917-20).Art work by John Singer Sargent; Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Strauss called “Salome” a “scherzo with a fatal conclusion.” Alison Pogorelc, who directed the Des Moines staging, and Steven Kemp and Jacob Climer, who designed the sets and costumes, seemed to have comedy uppermost in mind: this was a Hollywood Biblical epic gone to seed, with beefy soldiers outfitted in miniskirts and Herod sporting a variation on a Burger King crown. Chad Shelton wallowed happily in that high-camp role, while Norman Garrett generated countervailing nobility as Jochanaan. Sara Gartland, as the necrophiliac princess, gyrated fetchingly while delivering her taxing part in nimble, focussed fashion. The opera was heard in Strauss’s reduced orchestration; under David Neely’s baton, the musicians still made a splendid racket. As Gartland cradled a realistic replica of Jochanaan’s severed head, I wondered whether the experience was too intimate. But a proper “Salome” should make the stomach churn a little.

The Des Moines season also featured a world première: Damien Geter’s “American Apollo,” about John Singer Sargent’s putative affair with Thomas Eugene McKeller, the statuesque Black Bostonian who became one of the painter’s favorite models. This is an opera of a more traditional type: the libretto, by Lila Palmer, mixes poetry and prose. But it includes enough documentary material that it seems as much a work of observation as one of invention. If it isn’t Literaturoper, it’s Künstleroper—scenes from the lives of artists and their subjects.

Sargent’s sexuality remains a mystery. He obviously took pleasure in looking at naked male bodies; whether he ever went beyond looking is unknowable. Decades later, one of his models, Anton Kamp, described how Sargent shied away from physical contact when Kamp offered him a massage. (Ne me touchez pas! ) “American Apollo” presents a fantasy of what might have been—perhaps Sargent’s own fantasy. At the same time, it fashions a complex portrait of McKeller, who, as a part-time contortionist, submits willingly to Sargent’s gaze. (“I’ve done worse,” he comments to a friend.) What bothers him is that Sargent erases his Blackness, inserting his body into whitewashed mythological tableaux. Having more or less initiated a relationship, McKeller is resentful of Sargent’s constant travelling. Deciding that he needs a more settled life, he takes a job at the post office, as the real McKeller did. After the painter’s death, he gazes in wonder at the one truthful portrait that Sargent made of him, naked and unafraid.

Geter, himself a bass-baritone, writes beautifully for voices and elegantly for orchestra. His “Apollo” score fuses Coplandesque Americana, ostinato-driven minimalism, and languid blues. A couple of scenes pivot around “À Chloris,” the neo-Baroque chanson by Reynaldo Hahn, Proust’s sometime lover. Instead of trying to supercharge a static plot, Geter creates a glistening atmosphere of expectation and yearning. The fast-rising baritone Justin Austin gave a velvet-voiced, intensely charismatic performance as McKeller. The veteran tenor William Burden conveyed the nervous tensions behind Sargent’s suave exterior. Slyly negotiating between the lovers is the mighty arts patron Isabella Stewart Gardner, whom Mary Dunleavy, a mainstay of American opera for more than three decades, embodied with vocal agility and actorly finesse. Shaun Patrick Tubbs directed a production rich in Sargentine images.

The radiantly eccentric Gardner tied the weekend’s operas together: she adored Wagner, appreciated Debussy and Strauss, and believed in the fin-de-siècle religion of art. Sargent, she tells a skeptical McKeller, confers immortality: “In his eyes you’ll live forever.” A harmonic question mark at the end of the opera leaves the ethics of that transaction unresolved. ♦