Music Just Changed Forever – by James O’Malley

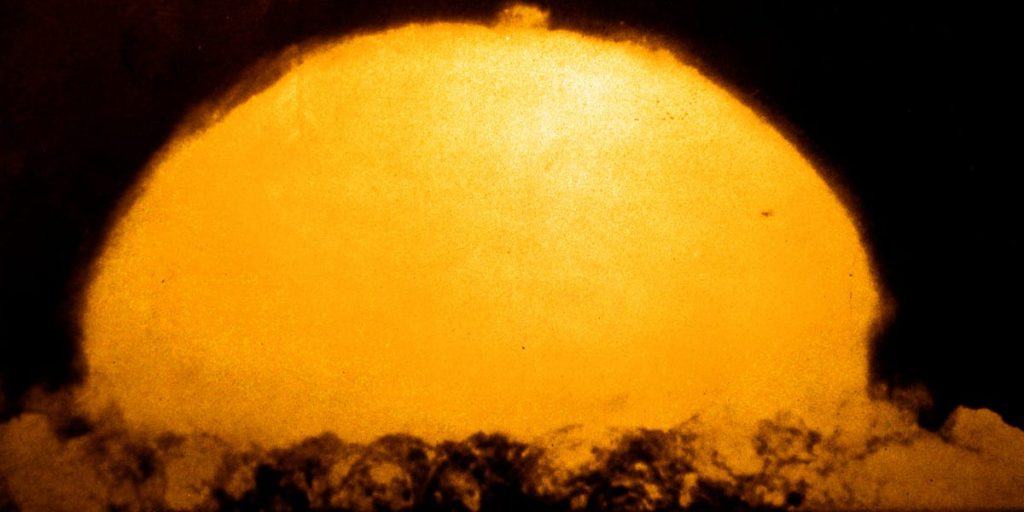

Imagine if after Oppenheimer successfully detonated the first atomic bomb, the rest of the world had just shrugged its shoulders and carried on as normal.

Because that’s what seems to have just happened in the entire field of human culture known as “music.”

A few weeks ago, a company called Suno released a new version of its AI-generated music app to the public. It works much like ChatGPT: You type in a prompt describing the song you’d like… and it creates it.

The results are, in my view, absolutely astounding. So much so that I think it will be viewed by history as the end of one musical era and the start of the next one. Just as The Bomb reshaped all of warfare, we’ve reached the point where AI is going to reshape all of music.

For some reason, though, it hasn’t triggered an avalanche of think-pieces in the broadsheet press. It hasn’t had music writers raising the alarm. There are no panicked, viral tweets and Instagram posts from musicians worried about their livelihoods.

I think this is strange, as you only have to hear the results of what it can do to see why it matters.

For example, here’s a summary of Donald Trump’s conviction in Manhattan… in the style of the broadway musical Hamilton:

(Note: This was made using “Custom” mode, where you provide the lyrics manually, and specify the genre you’d like. My top tip is to use ChatGPT to write the lyrics, and then paste them into Suno to turn them into music.)

Or how about this? I asked for a pop song “with country roots; catchy melodies, relatable lyrics, and storytelling” to describe someone trying to buy tickets for Taylor Swift’s Eras tour:

Now I know what you’re thinking: Yes, these songs aren’t great. But here’s the thing: They’re not terrible either.

If you were to casually hear them on the radio, you might not even notice they’re AI generated, though you might roll your eyes at what the kids of today are listening to.

However, I can understand if you’re still unimpressed. If this was the limit of AI capabilities there wouldn’t be many reasons for “real” musicians to lose any sleep over it.

But remember the complaints that the first AI image generators couldn’t get the number of fingers right? Or that the first deepfakes wouldn’t blink? We don’t hear those complaints any more because the technology very rapidly improved.

And there is every reason to believe the same is going to happen to AI-generated music.

I mean, forget my efforts above, if you listen to some of the “trending” tracks on the Suno homepage, then you’ll really get a sense for just how good this technology can be. Check out this blues track, or this 1920s dubstep, or this gospel song about eating a burger.

What’s important is that this is just the beginning. All of these songs merely represent the worst this technology will ever be. And Suno isn’t even the only option out there—the beta version of Udio, another tool to generate AI music, dropped within days of Suno’s release.

So let’s dig into what this transformation is going to look like—and how, for better or worse, it is going to change music.

When ChatGPT was first released, a common critique was to point out what it couldn’t do. It couldn’t write poetry, it couldn’t report the news accurately—and so on.

In fact, earlier this year big-shot New York Times journalist Ezra Klein said about AI: “I can’t for the life of me figure out how to use it in my own day-to-day job.”

Klein’s critique of AI misses the wood for the trees. It’s the same argument I’ve most regularly seen made by people with high status jobs: Think company directors, or top-flight journalists who write for prestige publications.

Of course AI can’t produce original, high-quality journalism, or plan a company strategy or make management decisions.

But look further down the corporate food-chain, and everyone else can see the benefits of AI clearly—mostly because they’re probably already routinely using ChatGPT on the sly to do their work.

For example, if your job involves boring admin tasks like reformatting address data to move it from one database to another, or building spreadsheets with complicated Excel formulas, or writing boilerplate legal disclaimers… then of course AI can make a big difference to how you work.

Even if AI was to develop no further than its capabilities today, it is already world-changing, as it represents billions of small, marginal gains in productivity. And I think this extends to AI-generated music. Even if AI music doesn’t improve any further, it already represents a profound change to the music industry.

Like the high status jobs I describe above, I don’t think it will make a huge difference at the “top” of the industry. Taylor Swift, Coldplay and, regrettably, U2, will continue to release albums and sell out stadiums. No one is going to stop you somehow enjoying Bono’s music.

But where I do think AI will make a difference are the billion other lower-grade circumstances where music is playing. If you need background music for your corporate health and safety training video, or you need a theme tune for your podcast, then it is a no-brainer to use AI instead of paying an expensive musician.

For better or worse then, AI will become the ubiquitous source of, essentially, “elevator music” for the entire world, and it will have terrible consequences for many people working in the music industry today. Musicians who earn a living making adverts or taking commissions from el-cheapo outsourcing websites like Fiverr are basically fucked—just like “low-level” visual artists and copywriters are by Midjourney and ChatGPT.

Nevertheless, I feel deeply, deeply conflicted.

On the one hand, yes, I place a high value on the sense of “authenticity” in the music I listen to. That’s why I’m a bad-ass punk rocker: To me, the purest form of musical expression is a circle pit in front of a sweaty band who can barely play their instruments, in a small, dank venue, where the toilets should be considered a public health hazard.

And because I’m straight-edge it is only in settings like this, waving my fist in the air as we collectively stick it to The Man, that I ever really experience something like a feeling of “transcendence.”

So this is all to say that I would love to be wrong about AI changing music forever. Music feels more compelling if it feels like it comes from the heart, and not a team of writers responding to market research.

But I also think that it is important to separate out what is real from what is just a comforting lie that we tell ourselves.

Because as much as we may hate to admit it, AI can elicit emotions in us, and I know this from personal experience.

A few months ago, my partner and I had a brief, upsetting experience with our cat, Hashtag. One morning, out of nowhere, something spooked her (the cat, not my partner), and she began to growl and behave very aggressively towards us.

We later learned she was experiencing something called “redirected aggression.” She was confused about what was upsetting her—and she had directed her anger at us instead. So for the next 24 hours, we were forced to keep Hashtag shut away from us, in the other half of the house, to give her time to chill out and realize that we’re not a threat.

Anyway, long story short, it turned out completely fine and she began behaving normally again. But we still had a long, distressing day, worrying that our beloved cat would hate us forever.

I explain all of this because of what I did a few days later, when I discovered Suno. First, I described the Hashtag situation to ChatGPT in some detail—explaining what happened, what Hashtag looks like, with a bunch of specific details. And then I asked it to turn this anecdote into song lyrics… Which I then put into Suno, which then generated a ballad describing the story.

And then I hit play.

The song it generated was like the others—passable in terms of its musicality, and very much in the midst of the uncanny valley. But then something strange happened: As the chorus kicked in, I felt a tear in my eye. The AI song was making me feel emotional.

And sure, on one level this is because I had specifically given it material to work with that is almost laser-focused on achieving this outcome. To an extent it was just repeating back to me a bunch of triggers that I had described to it.

But I’m not sure this is so different from “real” music. After all, we humans aren’t some special or unique part of the universe. We’re just meat-bags that respond to stimuli. Music isn’t special either. We all know that music can elicit emotions with just its musical qualities: When there’s a big key-change that gives us goosebumps, we’re no different from a cat that has been spooked by the garbage truck or the neighbors slamming a door.

To conclude, then, we’ve been given a glimpse of what the future looks like. We’ve witnessed the mushroom cloud plume into the air and I think it’s obvious that now that decent AI-generated music has been invented, the music industry will never be the same again.

And I’ll forgive you if you think that I’ve painted a bleak picture. Certainly if you work in the music industry, it is going to be a scary few years as things reconfigure.

However, I do think there are reasons to be optimistic about the future of music. Because the AI tools are also exciting.

In a sense, they are democratizing music. I am completely talentless, and gave up trying to learn the guitar when I was eleven years old. But with AI, I can participate in the joy of music creation.

And for skilled human musicians, AI also means new tools that could create entirely new forms of music, just as the electric guitar led to rock and roll, and sampling created hip-hop.

So when the AI era properly begins, it might not all be bad. We might start to hear things we’ve never heard before.

And won’t that be… good… for human creativity?

…And if you’re still not convinced, maybe this article would be more persuasive… in the form of a song?

James O’Malley is a writer and journalist covering politics and technology. His Substack is Odds and Ends of History.

A version of this article was originally published on James O’Malley’s Substack “Odds And Ends of History.”

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below: