In the key of 5G: the ‘dimensionalist’ who wrote a symphony for 1,000 phones | Classical music

Symphony concerts aren’t supposed to be like this. This week, the audience for the world premiere of Huang Ruo’s City of Floating Sounds will download an app and stand at one of four designated starting points on the streets of Manchester. Then they will select and play out loud one of 11 synchronised prerecorded tracks to the symphony on their phones as they stroll towards the Factory International Warehouse, following routes suggested by the app. There are constraints: if you’re sipping cappuccino on Canal Street and are five minutes late pressing play, what you hear will be synchronised with others parts already in play on other phones. Hopefully audiences will all arrive at the concert at the same time for part two of the experience, a live performance of the whole symphony.

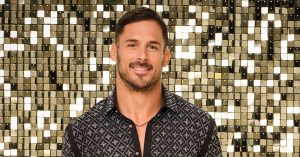

“Even in a Mahler symphony, the largest number of performers you could have is 120,” says the Chinese-American composer from his New York apartment. “In this case, there will be more than 1,000 – all of them will be creating the symphony together.”

But hold on, I say to Huang, aren’t mobile phones forces for evil in classical music concerts? Certainly, the recent controversy caused by audiences recording clips of classical performances at Birmingham’s Symphony Hall suggests that not everyone welcomes their intrusive presence during the live experience.

“Yes, phones can be distracting,” he says. “When my operas are staged, I don’t want people filming. I want them to be listening to the voices and reading the surtitles. But this piece is designed to use mobile phones to bring people together.”

Huang explains that the City of Floating Sounds app detects other users: “It’s like a traffic map. You will see where people are and you can decide whether to join them or not. What you are playing on your phone – say, the horn section – might blend in unexpected ways with another section played by someone else. There are so many ways that people’s participation drastically affects the outcome. No two performances can be the same.

“It’s planned as an outdoor piece. And if there’s noise, or rain, or traffic – it’s all part of the symphony.”

He hopes that passersby will be intrigued enough to join the procession. The whole thing has a Pied Piper vibe, with the twist that nobody is really in control of what happens. “Even the people walking around, who don’t know there’s a symphony going on but hear something flying around with the sounds, they’re already part of it. They will add to it unconsciously through their movements.”

City of Floating Sounds shares the boundary-blurring approach to music-making that guides Huang’s work. His operas, oratorios and symphonies draw, both politically and harmonically, on his Chinese heritage. He calls this approach Dimensionalism. “Music is not something left to right, front and back.” He wants to get away from the idea that concert music is something that happens in front of an audience, whose role is to consume the composer’s genius as mediated by musicians. Rather, he encourages audiences to creatively engage with performance.

Born at China’s most southerly point, Hainan Island, in 1976, the year the Cultural Revolution ended, Huang has fond memories of attending open-air performances of operas with his composer father and his grandmother. People would eat picnics in an informal way that is thrillingly alien to the western way of experiencing opera. That democratising impulse, he thinks, is worth reviving on the streets of Manchester.

Much of Huang’s music is overtly political. His staged oratorio Angel Island dramatised the sufferings of Chinese detainees at the titular Californian immigration station in the early 20th century. “Like a stray dog forced into confinement, like a pig trapped in a bamboo cage, our spirits are lost in this wintry prison,” sang his choir in Chinese.

Huang’s own transmission to America was easier: he studied at Oberlin and Juilliard conservatories and now lives in New York. He has made a name for himself with operas such as M Butterfly, which flipped the script of Puccini’s opera, giving its wronged Asian heroine agency. His operatic version of The Monkey King opens in San Francisco in autumn 2025, and he is currently working on a commission from New York’s Metropolitan Opera on an opera adapted from Ang Lee’s 1993 film The Wedding Banquet.

He claims City of Floating Sounds is political, too, just in a different way. “It is a piece written for the people of the city. Everyone who has a phone can participate, and everyone who doesn’t can still participate simply by experiencing it. That, to me, is a utopian vision of what our world should be.”

Once the audience complete their walk across Manchester, they will enter the concert hall to find the BBC Philharmonic encircling a space in which they can sit, lounge or stand. The orchestra will then perform the 43-minute symphony. Huang hopes the lighting engineers will realise his vision. “I gave them the idea of those big caves in Vietnam where light comes in through sinkholes. You walk in darkness, suddenly, you see a beam of bright light.”

During the performance, Huang hopes, phones will still be used. “I need to check with BBC, but I don’t mind people recording a little bit, as long as it’s not the whole thing. I would like them to share it on social media – so as to embrace as large an audience as possible.” He also encourages the audience to walk around during the performance – “this will add to the antiphonal, call-and-response effects going around the auditorium”.

But won’t it be challenging for the musicians if the audience are roaming about and filming? “We’re all really excited to see what it will be like,” says conductor Gemma New. “It’s our first experience of this kind of concert format.”

Huang recalls those childhood outdoor opera performances in a public square on Hainan Island. “The stars were huge. Each family brought some food and their own chairs. You ate while watching. But the important thing was that it was free.” That makes it sound very different from opera and classical music as they so often figure in the west – as expensive cultural products for conspicuous consumption. “It was a very eastern thing. The music was just a part of regular life.” How lovely if that eastern thing becomes part of Manchester, if only for a few nights.