Maritime Music Historian Stephen Sanfilippo on Sea Shanty Culture

During the early, quiet, and lonely months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many strange things occurred, among them a renewed interest in a near-dead genre of music: sea shanties. It started with one viral video on TikTok and it morphed, as trends do, to include other types of ballads and chants, leaving historians scratching their heads.

“They’re not shanties!” explains maritime music expert Stephen Sanfilippo in exasperation. “Those songs aren’t even work songs”—the type of folk music to which shanties belong.

Sanfilippo discovered the genre in the mid-1970s when, fresh out of the Navy, he started a folk music club at the Long Island high school where he taught. He went looking for old songs from the area; one led to another, and he has dedicated the half-century since then to collecting, performing, analyzing, and teaching songs from the sea.

To him, the songs that briefly went mainstream are more than just fun ditties or old-fashioned novelties. They’re important historic artifacts that give us a glimpse into how people in the past lived, worked, and thought of themselves. “Sometimes my students will say, ‘It’s just a song,’” says Sanfilippo. “But there’s so such thing as ‘just a.’”

The flash-in-the-pan glow of #ShantyTok has faded, but Sanfilippo remains committed to keeping maritime music alive. And though he doesn’t have high hopes for its future, his work can help illuminate the murky waters of contemporary life.

You told me that you’re particularly interested in the “music of the common people.” Work songs fall into this category, but what makes maritime music the music of the people? Why is it worth remembering this music and performing it?

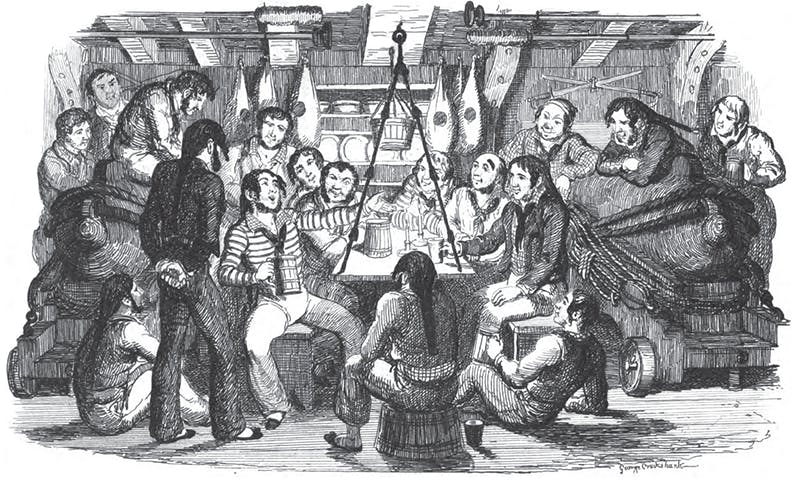

The sort of songs I sing are chanteys: the work songs of seamen. These are maritime songs, work songs, that are used to set the tempo and rhythm of body motion of particular tasks. They are akin to calling cadence when marching, which isn’t done by officers but by privates. It’s done by prison chain gang workers. And it’s not the guards who are singing it; it’s the guys who are swinging the sledgehammer. The songs are coming from the workers.

The ballads about shipwrecks and storms, often you’ll hear poetry critics call them doggerel. They’ll say they are formulaic. Of course they are formulaic! “We had a ship, and a storm at sea, and it was capsized. Thirty-five of us were killed and two survived.” That’s the formula. But when it’s lived experience, you can hear something in it that is eternal.

As a graduate student, your scholarship focused on Marxism and maritime music. What was the connection?

I wanted to do something with folk music and the “plain” people. I was also called to the idea that everything in nature is beautiful, and working in nature creates a body of music. The songs of dock workers, the songs of cowboys, even the songs of coal miners—they’re working in nature, too. They’re underground in the Earth. Doing this kind of labor creates a particular kind of music.

But that connection with Marxism didn’t quite pan out, did it?

The 1840s were a decade of labor radicalism; Europe had 17 revolutions in 1848. They were revolutions of the left against the established power of foreign occupiers, dukes, kings. My great-great-grandfather fought in the 1847 revolution in Germany and when he failed, he fled to New York. This is when Karl Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto. It was the time of Seneca Falls and the women’s movement. Things were happening.

I wanted to see if that kind of class consciousness existed among nautical workers or whalers. So I went to read 80 journals that were written by whaling hands, cabin boys, and ship’s carpenters. These were the guys writing, not the captain. I wanted to show that the seamen in the whale fishery—at least those from eastern Long Island— had a radical sense of class consciousness developing in the 1840s. I thought I would show this through songs.

Nothing made by man is more beautiful than a full-rigged ship sailing before the wind.

What I discovered is that none of these songs have a clear sense of class consciousness. There is conflict, but it’s not phrased in terms of class. Even in songs in which they had a poor person, it was describing one poor man in opposition to a single rich man. The stories in the songs weren’t phrased in terms of unified class consciousness. What I found instead is that they presented sailors in terms of their manhood.

In my thesis, I argued that there were several different types of masculinity represented in song. Seamen—by which I mean the hands, not the officers—were very different one from another. I wrote of them as “bourgeois aspirants,” who sought to earn money toward personal financial and status advancement; “secular libertines,” the stereotypical drunken, brawling, whoring sailor; and Evangelical Christians who, in the mid-1800s, were very much involved with social reform movements. They were the “liberals” of the day.

Why do you think sailors were not more radical or concerned with labor issues, given that they were working in a dangerous industry and likely being exploited by wealthier men?

Among other things, because human actions are often irrational. The simple answer is that people don’t really act in their own interest individually—and it’s hard to put thousands of mobile workers together. The geographical mobility of seamen, the going from ship to ship, and the overall impermanence of the work, be it in whaling, fishing, or commercial sailing, worked against the sort of organizing that could go on in mines and factories.

Keep in mind, I am not arguing that seamen were not conscious of being abused, and that they didn’t resist. Many—if not most—were always conscious of physical abuse, bad conditions, bad food, and bad pay, and found ways to resist. What I argue is that they did so through a view of abuse being an affront to their manhood, rather than through class consciousness.

What else do the songs tell us about the singers?

That they are not the stereotype we assign to them. Those who went to sea were diverse in outlooks and sensibilities. The same could be said for those ashore, especially as many of the ballads heard at sea were originally from farms or small towns.

Several times in our conversations you have said, “Everything in nature is beautiful.” How does this belief inform your work as a musician and historian?

“Beauty” doesn’t necessarily mean “pleasant to look at,” although most of “scenic” nature is. Remember, nature has no morality—so when a wolf kills and eats a lamb, or a tsunami kills thousands in a coastal town, or a shark eats the floating survivor of a shipwreck, that’s nature.

My father hated and ridiculed the word “picturesque.” “The picturesque farmers at work in their fields” means the impoverished peasants or serfs or slaves toiling endlessly for the landlords—or lords, or plantation owners. Those landlords don’t live in nature, but live off the toil of those forced to labor in a transformed nature for profit for the owners. But nature, in and of itself, is beautiful. It is God. What isn’t beautiful is the horrors of labor.

I hold that nothing made by man is more beautiful than a full-rigged ship sailing before the wind, the perfect coordination of nature and human mind and skill—but I must also remember that the seamen work in great physical danger, under severely harsh conditions of labor exploitation.

Do you think there’s a place for work songs in contemporary culture?

The roofers were here yesterday. The roofer was in his mid 40s and he had two guys working with him who were 18 or 19. They had two radios. They were listening to what Susan and I would call laundromat music—but they were not singing.

My grandfather and my father and my uncles, they bought abandoned farmland that was redlined for Italian immigrants. They built their houses on it, and while they were doing that, they would sing. They sang while they worked. What I see now with workmen is that they don’t sing.

When was the last time you passed a worksite and heard the workmen singing?

Do your students relate to the music you teach?

I taught American history through historic music at Maine Maritime Academy. And very interestingly, the young women got it. The boys didn’t.

We would go out on the schooner and I would teach them chanteying. We would haul the lines, raise the sail, and do it to music. We would do the work in accord with the rhythm and tempo of the song. The young women always performed better than the boys.

I think they had something to prove. Maine Maritime had only just started accepting women a few years before. There were people who felt they should not be there. They thought the majors that involved seamanship weren’t for women; they could be marine biologists or business majors, but they shouldn’t work with steam power or small vessel management.

Is the music you studied and revived a part of small towns in Maine or elsewhere?

It absolutely isn’t and it hasn’t been for over a hundred years. When Susan and I made the decision to live up here, and I got a job at Maine Maritime, people would say, “There must be a lot of great sea music up there.” And I said, “Only when I’m singing.”

What do you think is the future of work songs? Do they have a place in the 21st century that’s not just TikTok memes and watered-down, pirate-themed performances?

Let’s say that I’m not optimistic.

If by “work songs” you mean the historic call-and-response form of singing to coordinate body movement and muscle power by setting rhythm and tempo, I honestly see no future other than as something of a fabricated oddity among people who are somewhat “counterculture.” I can’t speak for other societies, but the United States has become a country of listeners who will listen to whatever the commercial music industry tells them to listen to at any given time.

When was the last time you passed a worksite and heard the workmen singing? When was the last time you passed a worksite and heard their radio playing music that had something to do with their work, or with the rhythm and tempo of their work? Music has become detached—or, to use a Marxist term, alienated—from work and from the worker. It’s relegated to background noise. Similarly, when was the last time you were in a store that played music over a PA system and shoppers sang along? Or in a doctor’s waiting room?

Back to chanteys, there are almost no sailing vessels today that use chanteys under sail. In fact, most people consider the chantey to be a mere outdated stereotyped curiosity, and if they sing anything, it’s almost always “What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor.” They sing it about 10 times too fast. It is sung as entertainment, not as a work song.

But is there any hope for this music and for young people? I work with high schoolers and there’s hope, I think, when you’re around them, partially because they’re always surprising me with what they’re interested in. Aren’t some of them interested in folk music and keeping the history alive?

I hope it’s not as bleak as I’m making it sound. I think there is hope. But it is frustrating.

We have a chantey sing upcoming here on Friday. I’ve been doing them for 16 years. And people come! I get a nice little audience. But there are no young people coming. And like I said before, people in Maine don’t sing. Nobody sings along. Nobody wants to sing these songs. They just look back at me. But I keep going. ![]()

Lead image: George Cruikshank / Wikipedia