Five of the best music books of 2023 | Best books of the year

Dance Your Way Home: A Journey Through the Dancefloor

Emma Warren, Faber

A dyed-in-the-wool clubber, Warren knows of what she speaks when it comes to the dancefloor: there is a lot of personal reminiscence in the endlessly fascinating Dance Your Way Home. But there’s also science, wide-ranging sociocultural history – folk dancing at Cecil Sharp House coexists with the rise of dubstep; Chicago footwork with the jazz-inspired ban on dancing in 1930s Ireland – and, more unexpectedly, a righteously angry polemical bent. Warren’s formative clubbing experiences were in the 80s and 90s, a golden era, simply because there were more venues. Clubs and youth spaces have since been decimated by councils and property developers, in a culture that, as Warren puts it, “fetishizes youth but doesn’t seem to like youth much”. She makes a compelling argument that dancing – and having the space to dance – matters: “You must let go of self-consciousness, embarrassment, pride and prejudice and embrace what you actually have.”

Curepedia: An A-Z of the Cure

Simon Price, White Rabbit

It’s tempting to describe the 448-page Curepedia as the ultimate toilet book for ageing goths, but that would be to underplay both the sheer breadth of information here – there are entries on everything from Albert Camus to intra-band bullying to Robert Smith’s relationship with the Japanese cult of kawaii, or “cuteness” – and how sharp its reading of the Cure’s oeuvre is. The opening entry on “the definitive Cure song”, A Forest, is more like a critical essay, involving The Wizard of Oz, Macbeth, the song’s ever-expanding length on stage and a contemporary critic’s appraisal of it as “moaning more meaningfully than man has ever moaned before”. Elsewhere, umpteen obscure facts are dug up – it’s hard not to warm to the sound of pre-Cure punk band Lockjaw and their big number I’m a Virgin – and the entry on Robert Smith’s regular suggestions that the band are about to split is hilarious. Curepedia functions as well as a definitive band history as it does something for that aunt still attached to her crimping tongs to keep in her bathroom.

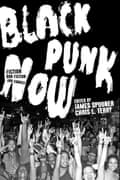

Black Punk Now

edited by Chris L Terry and James Spooner, Soft Skull

Last year, the Los Angeles Review of Books published an article by “Black punk” writer Mariah Stovall, detailing an “incomplete” list of punk lyrics that used the N-word. It featured a lot of legendary names: Patti Smith, Stiff Little Fingers, the Dead Kennedys and Crass among them – proof, if nothing else, that punk’s relationship with race has been historically fraught. It’s a state of affairs that makes this compendium of work – in which Black figures from the contemporary US punk scene reflect on their experiences via memoir, fiction, interviews, even comic strips – all the more fascinating. Edited by author Chris Terry and James Spooner, co-founder of the celebrated global festival Afropunk, it takes an impressively broad view of what constitutes “punk”. Defining the term, suggests contributor Hanif Abdurraqib, “is the least interesting debate that can be had” – and while what the writers in Black Punk Now have to say makes for occasionally, and not unexpectedly, grim reading, the book is ultimately a celebratory and inspiring collection.

Queer Blues: The Hidden Figures of Early Blues Music

Darryl W Bullock, Omnibus

Bullock has form when it comes to uncovering buried stories about music’s queer history: his brilliant 2021 book examining the preponderance of gay men in 1960s pop management, The Velvet Mafia, deservedly won awards. His exploration of LGBTQ figures in America’s early 20th-century blues scene delves deeper still: Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith’s bisexuality is well known, while Jospehine Baker’s impressive list of lovers has long been rumoured to include not just Georges Simenon and Le Corbusier but Frida Kahlo and Colette. But Bullock digs up a host of intriguing lesser names – Porter Grainger, the gender fluid Freddie “Half-Pint” Jaxon – and vividly draws a world of drag balls, rent parties and remarkably explicit homoerotic blues songs flourishing in the face of violent prejudice and illegality.

Reach for the Stars 1996-2006: Fame, Fallout and Pop’s Final Party

Michael Cragg, Nine Eight

This year has seen a glut of nostalgia for one form of 90s and early 00s music: Blur released a new album to critical acclaim, Pulp reformed for live shows to general delight and, at the time of writing, Oasis’s 1998 B-sides compilation The Masterplan, remastered and re-released, is heading towards No 1 in the UK album charts. But there were always other options, and Guardian writer Michael Cragg’s oral history of 90s and 00s manufactured pop feels perfectly timed: enough water has passed under the bridge that his interviewees, whether iconic or forgotten, feel able to speak freely. The sundry Spice Girls, S Clubbers and Girls Aloud paint a picture of a less self-aware, less polished pop era than the one we currently inhabit – it’s striking how distant it all seems – that’s alternately funny, shocking and profoundly depressing, but always enthralling.