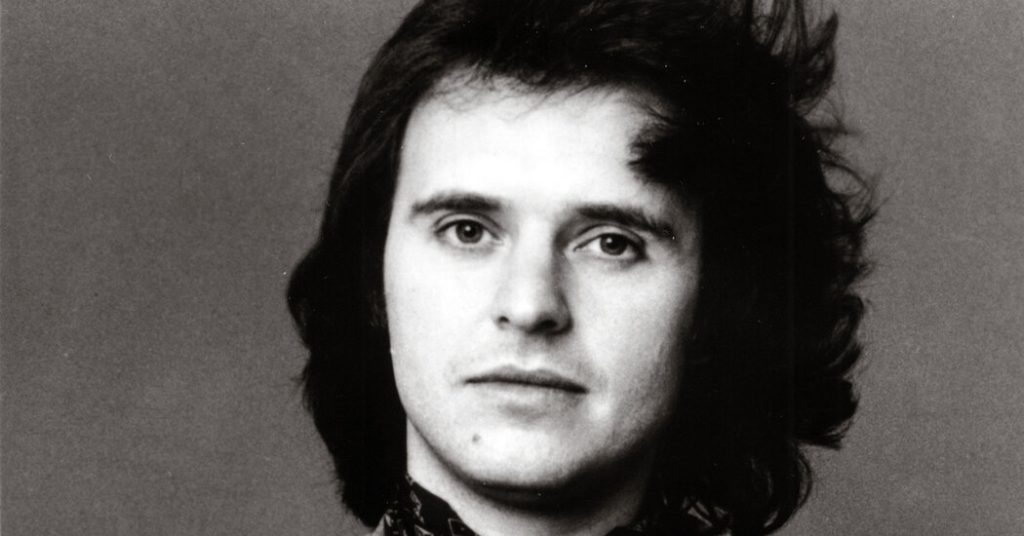

Gary Wright, Who Had a ’70s Hit With ‘Dream Weaver,’ Dies at 80

Gary Wright, a spiritually minded singer-songwriter who helped modernize the sound of pop music with his pioneering use of synthesizers while crafting infectious and seemingly inescapable hits of the 1970s, notably “Dream Weaver” and “Love Is Alive,” died on Monday at his home in Palos Verdes Estates, Calif. He was 80.

The cause was complications of Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia, his son Justin said.

The New Jersey-bred Mr. Wright rose to prominence in the late 1960s after relocating to London and helping to form the bluesy British progressive rock band Spooky Tooth.

He soon befriended George Harrison, with whom he would collaborate frequently over the years, including playing keyboards on that former Beatle’s magnum opus triple album, “All Things Must Pass,” released in 1970.

Their long friendship would have a lasting impact on both Mr. Wright’s life and his music. Mr. Harrison introduced him to Eastern mysticism, giving him a copy of “Autobiography of a Yogi,” by Paramahansa Yogananda, who helped popularize yoga and meditation in the United States, and Mr. Harrison traveled with him to India.

“That was his life path after that,” Justin Wright said in a phone interview. “Deep down inside of him, he was searching for something, and this was the answer for him.”

His spiritual awakening helped spawn “Dream Weaver,” a track from his 1975 album, “The Dream Weaver,” which hit No. 7 on the Billboard album chart and rocketed Mr. Wright to fame. The song was inspired by the yogi’s poem “God, God, God,” which includes the line “My mind weaves dreams.”

Mr. Wright begins the song with the lyrics “I’ve just closed my eyes again/Climbed aboard the dream weaver train/Driver take away my worries of today/And leave tomorrow behind.”

“Dream Weaver,” swept along by a wave of lush electronica that bordered on the interstellar, soared to No. 2 on the Billboard single chart in March 1976. The song became a soft-rock touchstone, appearing in such movies as “Wayne’s World” (1992) and “The People vs. Larry Flynt” (1996), as well as on a 2010 episode (titled “Dream On”) of the musical comedy-drama TV series “Glee.”

It was not the only smash hit from that album. That July, “Love Is Alive,” like “Dream Weaver,” rose to No. 2, conjuring the languid sexuality of the water bed era. Mr. Wright performed at stadium shows on the same bill as heavyweights like Peter Frampton and Yes, standing out among the guitar gods with his strap-on keyboard known as a keytar.

While his biggest hits became emblematic sounds of the 1970s, Mr. Wright had taken an unconventional musical approach on the album “The Dream Weaver.” He relied almost entirely on keyboard instruments, including a Minimoog synthesizer, as opposed to guitars, foreshadowing the synth-pop boom of the early ’80s.

“The theme of having only keyboards, drums, voices — and no guitars — came accidentally,” Mr. Wright said in a 2010 interview with Musoscribe, a music website. When he went back and listened to the demos he had recorded, he said, “I thought, ‘Wow. This sounds good. It doesn’t really need guitars.’”

Gary Malcolm Wright was born on April 26, 1943, in Cresskill, in northeast New Jersey. He was the middle of three children of Lou and Anne (Belvedere) Wright. His father was a structural engineer.

His mother helped instill in Gary an interest in music and acting, driving him to piano lessons and eventually to auditions. Their efforts paid off when he made an appearance on the seminal science fiction TV series “Captain Video and His Video Rangers” and later won a role in the 1954 Broadway musical “Fanny,” starring Florence Henderson.

“I originally came into the play as an understudy to the main role, and then I picked up the main child role,” Mr. Wright said in a 2014 interview with Smashing Interviews magazine. “I was only 11 and 12 during those years. It was an amazing experience to act and sing every night before sold-out audiences and sing with a full orchestral band.”

Within a few years, he abandoned the stage and screen “to be a normal kind of person in school, playing sports and Little League baseball and that kind of thing,” he told Smashing Interviews. While attending Tenafly High School, he played in various rock groups, including a duo called Gary and Billy with his school friend Bill Markle. Their single “Working After School” was played on the Dick Clark television show “American Bandstand.”

After high school, Mr. Wright attended William & Mary in Virginia for a year before transferring to New York University, where he switched his focus to medicine. After graduating in 1965, he briefly enrolled in medical school before moving to Berlin to study psychology.

Losing interest in a life in clinical practice, he went back to music, helping to form a band that built a following in Europe; at one point it opened for the rock group Traffic in Oslo. There he caught the attention of Chris Blackwell, the founder of Island Records. Mr. Blackwell summoned him to England to join a band called Art, which evolved into Spooky Tooth.

Spooky Tooth temporarily disbanded in 1970, and a year later Mr. Wright released his first solo album, “Footprint.” That album featured Mr. Harrison on guitar on the track “Two Faced Man,” which the two performed with Mr. Wright’s band Wonderwheel on “The Dick Cavett Show” in 1971.

In addition to his son Justin, Mr. Wright is survived by his wife, Rose (Anthony) Wright; another son, Dorian; a sister, Lorna Lee; and two grandchildren. His marriages to Christina Uppstrom, the mother of his sons, and Dori Accordino ended in divorce.

Along with his work with Mr. Harrison, Mr. Wright was a session keyboardist for musicians like Harry Nilsson, B.B. King and Jerry Lee Lewis, and he continued to record solo albums.

In the Musoscribe interview, he discussed his 2010 release, “Connected,” and the album’s hook-laden opening track, “Satisfied,” in terms that could have applied to “Dream Weaver.”

“The word ‘hook’ means drawing people into something,” he said. “When I write songs, I always try to make them that way — catchy — so that people will remember them. They’ll be more embedded in people’s consciousness.”